- Home

- Lori Majewski

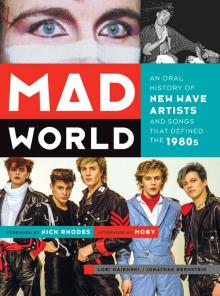

Mad World Page 2

Mad World Read online

Page 2

4. Bowie The voice, the hair, the videos, the clothes. The way he cut up words to construct lyrical collages. The way he juggled genres. Pretty much every musician who drew breath in the eighties owes everything to the career blueprint of David Bowie.

5. Top of the Pops It was a cheaply made, poorly produced BBC show that had been a staple of British Thursday nights since Beatlemania, and it didn’t discriminate. If you had a hit, you got to mime it in front of an audience that, at its eighties peak, grew past the 15-million mark. Spandau Ballet, Human League, OMD: All of them saw their cult followings swell and their chart positions soar because of TOTP. And most of them got so big that they could restrict their appearances and rely instead on …

6. Music videos and MTV MTV was originally conceived as a radio station with pictures—a network that sounded like American radio at the start of the eighties. The British bands who fled punk, embraced Bowie and disco, and who were hailed by the music press and appeared on Top of the Pops had no place on such a station. They were unknowns. They did not have significant live followings. The majority of them did not even have U.S. record deals. But the executives behind MTV were in such a mad scramble to get their new cable channel up and running that it never occurred to them to question whether there were sufficient videos by Journey, Loverboy, and Rod Stewart to fill out 24 hours of airtime. As it happened, there were not, which is why the network was forced to shift its gaze to Europe, where weirdly attired groups with indecipherable accents cavorted in overblown mini-movies. City by city, suburb by suburb, adolescent record buyers began pledging allegiance to Duran Duran, Eurythmics, and the Human League. A Flock of Seagulls followed, as did Depeche Mode and Simple Minds.

Were the artists ridiculous? Was the music overproduced? Was the influence of Bowie ubiquitous to the point of being suffocating? Guilty on all counts. But it was also an era of imagination, vaulting ambition, and incredibly memorable songs. The accidental British Invasion of the eighties created a world in which Madonna, Prince, and Thriller-era Michael Jackson thrived.

We’re not saying great pop songs aren’t written anymore. It’s just that a decade of TV talent shows has given us a breed of performer whose only personality characteristics are humility, gratitude, and an undying love for their mommies. And when those humble, grateful performers embark on their careers, any remaining traces of their individuality and autonomy are auto-tuned out of them by superstar producers.

Mock and ridicule the excesses of the eighties if you want, but don’t try and deny that the stars of the era had personality. They may have been pretentious, pompous, and absurd, but it was their own pretension, pomposity, and absurdity. They didn’t have to bow their heads and nervously wait for the approval of a jaded record executive on a judging panel. Love or hate them, they were their own glorious creations. They were not boy bands. They were not manufactured. They were, for better or worse—worse being Kajagoogoo—the last of the big pop groups.

And their songs are still with us. You might laugh at them. You might yelp your way ironically through them at karaoke (in which case, put this book down. No, don’t. Your money’s as good as anyone else’s. It’s just your personality that’s lacking). Or you may unabashedly love them. But you never forgot about them.

Neither did we, which is why we wrote this book. We wanted to know the stories behind our favorite songs from our favorite era. To find out, we phoned, Skyped and met up with some of our favorite acts, and we ended up reminiscing about a whole lot more: the good times, the bad times, the hits, the flops, the money, the madness, the fights and, of course … the hair.

Here’s what this book isn’t: a definitive oral history of the new wave era deserving of its own floor in the Smithsonian. Here’s what it is: a random sampling of the decade, a bunch of snapshots summing up songs and artists embedded in our hearts. Your favorite eighties anthem might not be here; some obscure oddity might be in its place. But then, there might be something you haven’t thought about in years and can’t believe we were smart and resourceful enough to include, i.e., not “The Safety Dance.”

Here’s how it works: Each chapter begins with an introductory paragraph that puts the artist and song into a broader context—where and how they fit in with the culture, their enduring influence, and so on. Following that, we, the brilliant authors, provide individual commentary. Who are we, and what makes us think our opinions matter? Good question! We are Lori Majewski: American, obsessed past the point of sanity with Duran, Depeche, the Smiths, New Order and … you get the idea. She loves it all, unconditionally, wholeheartedly, and hysterically. We are also Jonathan Bernstein: Scottish, sour by nature, too uptight and suspicious of emotion to declare himself a fan of anybody, but a staunch supporter of the sheer oddball nature of the era. Next, the artists recall their songs, careers, regrets, memories, and journeys. Although we conducted these interviews in time-honored Q&A style, we run the answers as edited monologues. All of the interviews were conducted individually. Finally, each chapter concludes with a “mixtape” in which we recommend similarly themed songs by other artists.

We’re all too familiar with the strikes against the eighties: It was the video decade; the visuals took precedence over the music; it was all style over substance. The prosecution rests. We can’t refute any of these charges. However, no music video, no matter how gargantuan the budget or drug-crazed the director, can salvage a dud song. And none of the 36 songs in this book are duds! These are the new classics: 36 songs that still have life left in them, that don’t sound like relics, and that continue to get airplay and show up on soundtracks, compilations, and reissues. We fought over these 36 songs. We fought even harder over the other 36 we had to leave off the list. And there’s another, other 36 we’re still grumbling about having had to jettison. Toni Basil, your day will come!JB/LM

“KINGS OF THE WILD FRONTIER”

dam Ant was the male Siouxsie Sioux. Like the Banshees, the Ants were among the last of the original U.K. punk bands to sign a record deal. Like Siouxsie, Ant cultivated a darkly sexual, proto-goth persona, enjoyed a voluble, devoted following, and refused to skimp on the eyeliner. Unlike Siouxsie, Ant got no respect. In the late 1970s, Britain was able to sustain four weekly music papers, all of which wielded a degree of influence and regarded Adam and the Ants as a lamentable vehicle for a narcissistic phony. They labeled Ant an inauthentic buffoon, an art student dabbling in S&M imagery. The Adam and the Ants responsible for the likes of “Whip in My Valise,” “Red Scab,” and “Deutscher Girls” deserved most of the derision they received. But the Adam and the Ants who recorded the likes of “Kings of the Wild Frontier,” “Dog Eat Dog,” and “Antmusic”? They’re a principal reason this book exists. When Ant decided to retire the empty shock value of his previous incarnation, to recruit co-conspirator, guitarist, and former Banshee Marco Pirroni and to launch an all-out assault on the mainstream, he did it in the weirdest way possible. None of the musical and visual elements Ant plundered for his reinvention pointed to his subsequent ascendance to teen idol status, but the totality of his image, his theatricality, and the sense of community in his calls-to-arms struck a massive chord. Refusing to settle for life as a stalwart of the independent circuit unshackled Ant’s imagination and his ambition. He went from a punch line in bondage pants to the man who would be king.

JB: Forget the white stripe and the line “I feel beneath the white, there is a redskin suffering from centuries of taming.” The only tormented minority Adam Ant truly identified with was the Entertainer. Adam and the Ants may have rebooted themselves with a chaotic new look and a vibrant new sound, but the dismissive treatment the old Ants had received at the hands of the media still rankled. “Kings of the Wild Frontier” is a squeal of outrage from a flamboyant, full-color performer freeing himself from a tawdry, foul-smelling, monochromatic post-punk universe. Ant basically had one theme: The artifice of show business was infinitely preferable to the music press–mandated notion of credibility. He rehashed that sent

iment in “Prince Charming,” “Stand and Deliver,” and “Goody Two Shoes.” But he never sounded so alive, so energized, and so hell-bent on writing his own legend as he did in “Kings of the Wild Frontier.” It was a combination of the liberation he felt about throwing off his old (white) skin and the fact that no one had any expectations of him. It was the lingering resentment over the devious way momentary Svengali Malcolm McLaren made off with three of his Ants to form Bow Wow Wow. (For more on this sordid tale, see our Bow Wow Wow chapter on this page.) It was the way Marco Pirroni’s guitar twanged over the drumming duo’s thundering Burundi beat. It was the way Ant announced his second act with the declaration “A new royal family! A wild nobility! We are the family!”

LM: There were two singers who shook me up in the way I imagine Elvis Presley did my late-1950s teenage counterparts: Michael Hutchence and Adam Ant. Neither was textbook handsome like, say, John Taylor or Rick Springfield. And while both were usually bare-chested under their tough-looking leather jackets, neither was what you’d call buff. Still, the way they moved onstage and made eye contact with the camera suggested they were sex incarnate. Watching these two, I was never so sure of my heterosexuality. But while Hutchence’s deep, conversational singing voice always sounded bedroom-ready, Ant was capable of screams and yelps that suggested you caught him in the middle of the act. That has to be why Sofia Coppola chose “Kings of the Wild Frontier” for the scene in Marie Antoinette in which the queen finally finds coital satisfaction while cheating with the studly Count Fersen. When I met Ant for our interview, he made his entrance wearing eyeliner and eyeliner-drawn sideburns, and a pencil mustache that was more Captain Jack Sparrow than Prince Charming. Still, I couldn’t help staring into his blue eyes and thinking, Don’t you ever stop being dandy, showing me you’re handsome.

ADAM ANT: I was doing graphic design at Hornsey College of Art. I started up a college band called Bazooka Joe. I was playing bass and writing and singing. Bazooka Joe did their debut in London at St. Martin’s College of Art in November 1975. That was the night I saw the Sex Pistols—they were the support act. They looked great, dressed in really great clothes. They played very simple songs: Small Faces and Who covers and a few of their own. It wasn’t screaming, 15-minute guitar solos in denim-clad outfits; it was, like, 10-second guitar solos. They were really tight. And they had a complete disregard and contempt for the audience that I’d never seen before and quite liked.

That was the catalyst. I thought, Something’s happening here, and it’s not that difficult. There were very few people who were interested in the Pistols at the start. Bazooka Joe were too set in their ways—they were a rock band and didn’t like punk. So I left the band that night and formed the Ants, and that was the start of the career. That was the sort of influence the Pistols had on people. Most of the people in that room went on to form their own bands.

The early Adam and the Ants got a lot of criticism from the media, so much so that we didn’t get signed. We had a large following, but they didn’t care about that. They just didn’t like the idea of signing me. Our first big single, “Dog Eat Dog,” was more or less a general assault on the public. I thought our music was better than everyone else’s, as every band does, and I put it lyrically. “Only idiots ignore the truth” was a result of being ignored for three years.

In 1979 Malcolm McLaren approached me at a party, and I was quite surprised, really. I think he’d been watching what we were doing and certainly liked the following. After the Pistols, I think he wanted that following. I enjoyed my time with Malcolm. I learned a lot—his theories became very useful to me in my dealings after that time. He stripped it down to a realistic approach to the music industry: simple things like don’t be so esoteric; if you want a hit record, put your face on the cover; the structure of a good hit single. He was a great historian of music, which you wouldn’t have thought. He came across as an anti-music person, but he actually knew a hell of a lot. And he became a friend, so it was a great loss when he died a few years back.

It wasn’t exactly as Zen as that, though. I think he had the idea for Bow Wow Wow before he met me. It seemed like a mutiny at the time. But if it had to happen, it was the right time to happen. And no one can force you to do that. The other three saw a better opportunity to work in their own setup, so they did. I could never have worked for Malcolm. Bow Wow Wow was pretty much Malcolm plus them backing his musical ideas. But they went off and did Bow Wow Wow, and I thought they did some good work. It also gave me an object of competition. I had my eye on them, and we had to blow them out of the water, and I think we did.* Annabella [Lwin, former Bow Wow Wow lead singer] is actually a friend of mine.

My songs tend to be a travelogue of my life. Every album has a different look, a different sound, different lyrical content. The hard, simple punk stuff of the first few singles was completely different from the first album, Dirk Wears White Sox, which was quite a weird record. It certainly wasn’t a punk record. Then Kings of the Wild Frontier and Prince Charming—every album’s been different from the one before.

I liked Lenny Bruce a lot. I’d been listening to him a lot in the late seventies, and Jackie Mason too. And during an art history course, I’d tapped into the Futurists, who were doing some amazing work in sculpture. They all basically got killed in the First World War, so there was only a tiny body of work. I didn’t particularly like their politics, but I thought their art was fantastic, marvelous. They were like the punk rockers of the art world, doing weird stuff, ballets and musicals where none of them could play at all. They’d just be blowing trumpets and beating each other up.

What I tapped into then and still do is history. I’m well up on the Regency dandy period. I love certain parts of military history: Napoleonic history, the Charge of the Light Brigade. I took all of these images that I’d grown up with and made a mutant, a hybrid. Punk got really dark by about ’79—really druggie, really political, very gray, very nasty. I hated it. So I wanted to do something that was the reverse: colorful, heroic. Pirates and Native Americans were, in their pure essence, quite heroic themes. I’d done my homework on them, then blended them into this idea, and the music matched.

“Kings of the Wild Frontier” is really a mark on all sorts of colors and societies where you feel held back. The lyrics “I feel beneath the white, there is a redskin suffering from centuries of taming”—it’s not just the color of your skin; it’s the class you’re born into. If you’re born poor, if your parents don’t have any money, it’s quite a hard life for you. The Apache war stripe was a declaration of war, as I saw it, on the [record] industry I was up against. They were the enemy. But it was also quite a spiritual thing. I gained a great deal of comfort from studying their ways and philosophies.

* LEIGH GORMAN, Bow Wow Wow, formerly of Adam and the Ants: I remember Adam came on Top of the Pops with “Dog Eat Dog” with his white line on his face. I thought, That’s it. He’s done it. We’d just put out “C30, C60, C90, Go.” The guy at the record label called up Malcolm and said, “These sales figures don’t match your chart position. You guys should be at number 14 or 12 right now, and you should be going on Top of the Pops, but they’ve held you back.” So we went over to EMI and trashed the place. I think we threw Cliff Richard [gold] records out the window. Malcolm was trying to create a stunt like the Pistols. It completely backfired: They didn’t promote the single. And Adam comes along with his image, his better-sounding production, and his more innocuous lyrical subject, goes on Top of the Pops, and everyone goes nuts.

STYLE COUNCIL

“[Michael Jackson] phoned me up and asked where I got the jacket from.” Ant says, “I told him where to go, and he went and got it. It’s a hussar jacket, a theatrical costume from Bermans in London. I sent him down to my friend who worked there. He said, ‘I want an Adam Ant jacket,’ and they gave him one.”

When I came to the USA in 1981, I had a complaint from a Native American society in New York City, and I had to meet with them about it. They

were concerned that I was using the stripe. They thought it was just me stereotyping Indians—I don’t use the word “Indians”; it’s “Native Americans.” So I went to see them, I spent the day, and I said, “Look, come and see the show, and if you think I’m using it in a derogatory way, I’ll take it off.” They came to see it, loved it, and it was all right. I got the go-ahead. I wouldn’t have felt comfortable if I thought I was offending people for no just reason, the fact you just don’t know your subject. My father was a Romani Gypsy, so I’m very up on the way the Gypsy society is portrayed. They’re quite dismissive—they say “Gyppo,” which is a slur. It’s not nice. So having dealt with that in my family, you respect other people.

I write songs for me. I don’t write songs for other people. As far as “Prince Charming” is concerned, I was addressing myself. I wanted to present myself in a good way. My granddad may not have had a lot of money, he may have been born in a caravan, but he looked very smart, very clean, and that stayed with me. That was part of the “Prince Charming” idea. “Ridicule is nothing to be scared of” was a line I felt was quite apt, certainly being in the pop business.

“Goody Two Shoes” was a manifesto about what was happening at that point. “You don’t drink, don’t smoke”—purely because I didn’t drink or smoke, people made assumptions. I thought that was quite a good lyric. And it worked. That certainly broke me in the States. “Two weeks and you’re an all-time legend / I think the games have gone much too far,” that was almost like saying, “Look, I’ve had enough of this,” and I took all the makeup off.

When video came along, right there, there was a revolution that I was able to embrace. I had a film school training, so I storyboarded them myself, and I could co-direct them. The video became as important as, if not more important than, the music. It didn’t hurt that I had had a video go out to homes in the USA before I arrived. When I did my first American tour, our record company commissioned a pirate ship to sail us up the Hudson River to our New York concert. They’d seen what was going on on MTV. People were dressing up like me before I even got here. That wouldn’t have happened before video, because I would have had to go out and do the tours first. But those music videos … you can’t put that on the radio.

Mad World

Mad World